Last night in UC Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall, Seun Kuti had the crowd on its feet and dancing in the aisles to his version of Afrobeat, the music pioneered by his legendary father, Fela Kuti. While Fela! The Musical has brought new attention and perhaps a new audience to Fela’s music and story of protest, the late Black President’s legacy also survives in the music of his son, Seun (pronounce Shay-oon). The youngest of Fela’s children, Seun got his start playing with his father’s famous band, Egypt 80, in Nigeria in the early 1990s at the age of eight. I had the opportunity to talk with Mr. Kuti a few days before his Cal Performances appearance about his beginnings, his band, and their responsibilities as an institution of African music. Raised at his father’s commune-like, semi-independent state, The Kalakuta Republic, and singing regularly with the band in the Africa Shrine, Fela’s club in Lagos, Nigeria, Seun’s youthful experience was far from typical: “All my friends went to bed, everybody but us, we went to the club to perform.” As a young singer and opening act for his father, Seun made his impact with Nigerian club goers, “Everybody likes to see a little kid. Sometimes people would come on stage and dance with me.”

When asked how he began to learn to play music, he explained that his father emphasized discipline and correct training. “I didn’t even start playing my horn until after my father’s death,” he said, “I was mainly playing piano when I was a young kid. My dad said that before I could play on any of the other instruments you have to be classically trained up to grade five on piano – that was the rule.” The wisdom of this rule became clear to him as he matured: “When you do that and you pick up your horn later on, you can teach yourself the books.”

After the death of his father in 1997, Kuti took over the leadership of Egypt 80, the band heard on many great Fela Kuti records such as Teacher Don’t Teach Me No Nonsense and Army Arrangement. In 2008, Seun recorded his first album, Many Things, with the band, a recording that was praised for its energy and message of protest, qualities that characterized Fela’s music. During the summer of 2011, his second album, From Africa With Fury: Rise, heralded the emergence of a new, mature artist with a more personal approach and sound. Between albums, Seun underwent considerable development as a man and musician. “My musical journey was a big part of my life journey at that time in terms of becoming another person and understanding music, life, politics.” He learned to channel his rage and frustration with the problems of contemporary Nigeria, especially foreign corporations and oil companies, with a more sophisticated musical presentation. “I always want to make a better album,” he declared, “Always, you know? I’m working on my next album now and the first things for me, the criteria: are any of these tracks sounding like something you’ve done before, are you improving on the things you’ve done before? I believe in constant improvement.”

When asked how he builds a composition from an idea to one of his massive, rhythmic work-outs for 14 musicians, he said, “I can’t divulge all of the classified information, but every musician has his own way. You get an inspiration, you hear a sound, you create a vision for that sound in your head. Now the hard work is making that vision a reality, writing it out. I give a lot of credit to my band because if I compose a song and the band can’t play it, then what’s the point? We’ve been playing for so long that we have a certain kind of connection. It’s makes everything easier in terms of where we go from there. Egypt 80 is literally the longest surviving African band. This fact makes it an institution that deserves immortality. Half of the band are potential band leaders themselves. I’ve never stopped anybody in the band from exploring new avenues to improve themselves as musicians.”

His American tour has been a grueling string of one-nighters in locations all over the country. I asked him about the American audiences he has played for and how they compare with those at Africa Shrine in Nigeria. He said, “For me they’re the same all over the world if you go to a place and your audience is content to sit down, and look at you all day and clap, and at the end give you a standing ovation, and then you go to another place and they want to dance all night. In Africa, in Nigeria, they’ve been experiencing Afrobeat for 50 years. They know what they want.”

When Egypt 80 took the stage on April 19, 2012, in Zellerbach, they were greeted politely. Comprised of older gentlemen of Fela’s generation with a few younger faces interspersed, the band began with “African Soldier,” a tune that was announced and led by the young trumpeter Olugbade Peter Okunade. A wandering trumpet solo, balance problems, and an inaudible solo from baritone saxophonist Abidemi Adebiyi Adekunle, plagued the opener, a fact that did not bode well for the evening’s performance.

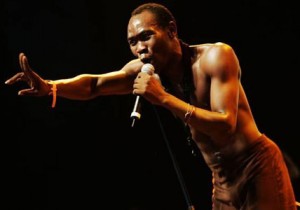

Everything changed when the tune concluded and a long-legged Seun, elegantly dressed in a tight-fitting lilac dress shirt and blue bell bottoms, made his entrance. Oozing confidence, his appearance stirred the audience and rallied the band’s flagging energy. It seemed clear that this band of veterans relied heavily on the young frontman for leadership and inspiration. Throughout the evening, Seun exhibited a collaborative spirit and lack of ego in musical matters, ceding the spotlight to other instrumental soloists or joining the horn section for ensemble passages. Taken along with his charismatic stage presence, his effectiveness as a bandleader was obvious.

From that point, there was a gradual ratcheting up of energy, from lively tunes to a rousing, cathartic performance of “Mr. Big Thief,” on which both Okunade and Adekunle redeemed themselves with aggressive, driving solos. Oscillating between two pitches or repeating short phrases, Seun often utilized a rather narrow melodic vocabulary in his many, short saxophone solos, a choice that served the band’s building momentum well. When he set his sax down and danced, chanted, or pounded his chest singing, “Oh yes, we must rise!” the young leader aroused the respectful spectators and brought everyone into his impassioned here and now. Like his father, Seun also used the stage as a pulpit and spoke about the financial crises in Nigeria and America and how the differences were just a matter of scale; that we are all victims of greed and corruption by politicians and corporations. Obviously his message to the 99% found many a sympathetic ear with the Berkeley crowd and his anthem decrying the crimes and abuses of Nigeria’s former president, Olusegun Obasanjo, “Mr. Big Thief,” threatened to blow the roof off. Seun, marching like a soldier, jerking like a man possessed, and shimmying his feet like James Brown, displayed seemingly inexhaustible energy reserves. Knowing he does this night after night while traveling all over the world is a difficult and impressive truth to apprehend.

Zellerbach seemed a strange choice of venue for this kinetic music and the leading man’s stirred-up presentation-style, but we must be grateful that Cal Performances brought this African music to our region, regardless of venue, in the persons of Seun Kuti and Egypt 80. The good sized audience was highly appreciative if timid, at first, to participate. As concert etiquette prescribes in a place like Zellerbach, many audience members kept to their seats while others filled the side aisles to shake along with the music. After the band played “The Good Leaf,” a change had occurred and there were clearly more people on their feet than seated.